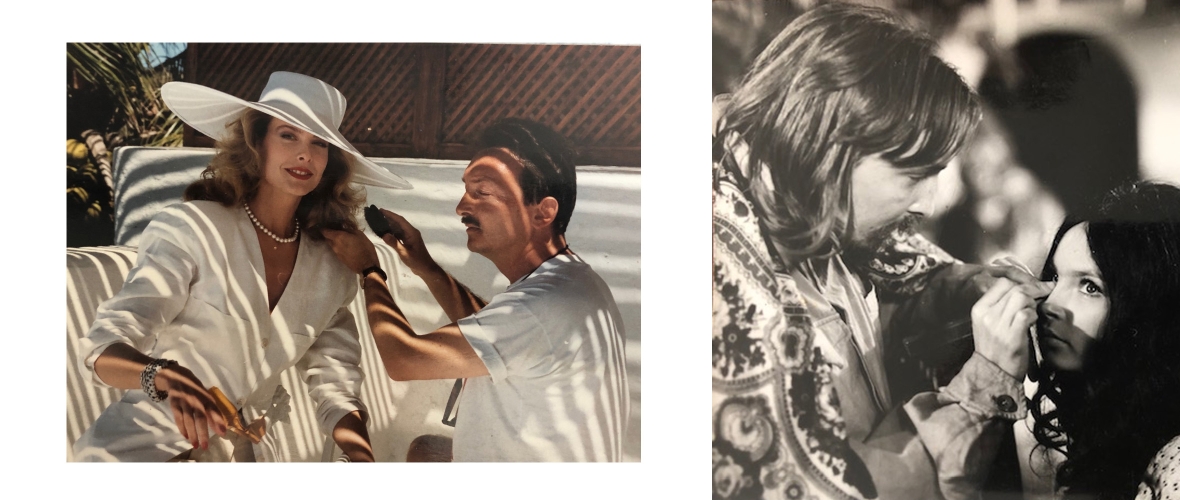

I feel that often the role of make-up artists is underestimated in the process of creating a film, or is overshadowed by the enormous amount of effort that also goes into creating the set design, visual arts or costumes. And it is often in the make-up room that characters are created – a small made-up scar, a wrinkle, or a mustache can add dignity or take it away, they can make a character more mature, softer, aggressive or frivolous. Not to mention full-bodied creations, as in “Dracula” or “Pirates of the Caribbean”.

This is precisely who I am – a soldier, sailor, bandit and priest – and each of them has a different role.

Are you more of a priest or a bandit?

It depends on the scenario. And sometimes you have to combine these roles – I start with a priest and end with a bandit. And the bandit can also become a priest.

So you are transforming yourself when creating films.

Of course. There are films where the plot time spans several decades, so you have to take into account the anatomy and biology to figure out how the actor will age. And this is linked to the whole role, to the script, to whether his character is an upper-class person, a count or a villager. The signs of aging will be different for everyone. A villager will age faster, because of the nature of his work. A well-cared-for doctor from the city, on the other hand, will age differently.

How do you approach the job?

First I read the script, and then I sit down with the director, costume designer and cinematographer. For me, cinematographers are very important – without them, there is no film. A film is the transfer of a story to a picture, it is like painting. For the viewer to get a good understanding of the story on the screen, everyone’s work must be harmonized. Working with a cinematographer also gives me an important tool, which is light – it can help but also ruin the image of a character, of his or her face.

Which film was a turning point that allowed you to undergo the transformation you mentioned above?

That’s a very difficult question. As far as films are concerned, certainly “Schindler’s List”, which opened new opportunities for me in the world, and brought further offers to work with actors and directors. But it was not an easy film because of the story itself and the atmosphere of the Holocaust on the set. I was still greatly influenced by Tykwer’s “Perfume” and Haneke’s “The White Ribbon”. “Perfume” was, so to speak, a complete job – it involved both usual make-up and special effects. This film also left a strong mental imprint on me. It was a big historical undertaking, the era of the late 17th century. There were many elements that drew me strongly into the film. I was certainly also strongly affected by working with prominent directors who were also very demanding. You then have to give your best. And we should remember that no one cares what happens off-screen. That’s why I always say that the truth only comes out when we sit down and watch this movie we made. The screen exposes the truth. The camera is ruthless, so the challenge I set for myself is to be vigilant, because others don’t have to see but I have to see and be constantly on guard. And that’s why I have to be on the set, next to the director, next to the camera, to control it all even better. The cinematographer thinks about the light, the director thinks about the scene, how the actors should act, and the costume designer thinks about how the dress and shoes fit. And make-up is my responsibility, although, of course, it is collective work. Before we start working on a film we determine how an actor will look in given scenes, or in given years. There are films where certain things are implemented on set. There are also those directors who can’t imagine what the actor will look like when we change his hair and age him – they have to see it with their own eyes. There are also sets where all the rehearsals of the actors’ make-up and looks must be done in advance.

How would you describe Waldemar Pokromski’s style?

Well, actually I could say it’s “no make-up” but now many people are trying to work that way. In general, the idea is to make the make-up not visible. I’ve created some innovative effect techniques, for example I came up with internal facial inserts that give a fattening effect, great especially for roles where the actor has to gain weight or undergo a visible transformation. This idea of mine, was used for the first time in America, and was considered cost-effective and giving a great effect because we didn’t have to create layers from the outside, we just “fattened” the actor on the inside.

What are the trends and styles in make-up today?

The way of emphasizing beauty hasn’t changed particularly, as for women we still emphasize lips and eyes – these are the two most essential elements of the face that dominate when we look at it. And they have always been emphasized in the history of cinema. Colors or hairstyles are subject to notorious modifications. I’ve been testing a lot of beauty products lately, and I like to work using Dr Irena Eris cosmetics – they are gentle in texture and have very subtle colors, very useful in film make-up.

Who is your make-up guru?

In the States there has long been a division between classical and special effects make-up artists. In Poland, we do both. Both in the States and in the UK there are great make-up experts, e.g. English makeup artist Morag Ross, who has worked with Cate Blanchett for years, or Christopher Tucker, with whom I apprenticed in London. I also highly value Dick Smith and Rick Backer. How did they get to this point? It is certainly a combination of great talent and a bit of luck. This was also the case for me – I worked on “Captain America” because they happened to be looking for local artists working in Germany.

With your dislike of math, do you prefer today’s epic undertakings that require a lot of logistics or intimate, personal cinema?

At the moment I prefer smaller films that give more time to think about the character, and more time for creation. I just choose the less busy productions now.

What are your plans for the future?

With this industry, you never know. I always say that the film starts with the first clapping of the clapper sticks. I’m involved in developing my son’s [Mikołaj Pokromski] project “Too Big for Fairy Tales” and I’m also currently working on Gośka Szumowska’s “I Like to Come Back” film which is being made in collaboration with the Dr Irena Eris brand.